Howard Zinn reports four deaths in his A People's History of the United States (1980) and quotes part of Spies' leaflet:

Revenge!This circular was published and distributed the evening of 3 May 1886 and set the stage for tensions the following evening at Haymarket Square. According to Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen, A Patriot's History of the United States (1994), "August Spies set the table for more violence" (439). Schweikart and Allen quote the first three sentences of the circular, "Revenge! Workingmen, to arms! Your masters sent out their bloodhounds!" (439).

Workingmen to Arms!!!

...You have for years endured the most abject humiliations, ... you have worked yourself to death ... your Children you have sacrificed to the factory lord--in short: you have been miserable and obedient slaves all these years: Why? To satisfy the insatiable greed, to fill the coffers of your lazy thieving master? When you ask them now to lessen your burdens, he sends his bloodhounds out to shoot you, kill you!

... To arms we call you, to arms!

as quoted in Zinn, 270-271 (ellipses in Zinn)

Tensions had been building for months. On one side were the police, the state militia, the leaders of industries, a "Citizens' Committee" that met daily to plot strategy. On the other side were members and leaders of labor unions. The Chicago Mail, Zinn tells his readers, had suggested on 1 May watching and making an example of Albert Parsons and August Spies of the International Working People's Association: "Keep them in view. Hold them personally responsible for any trouble that occurs. Make an example of them if trouble occurs" (as quoted by Zinn, 270).

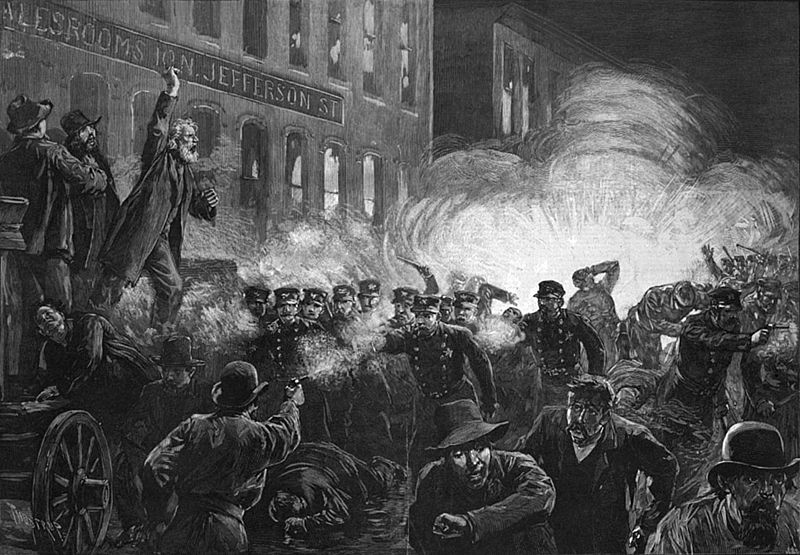

Despite the militant rhetoric, the protest at Haymarket Square was peaceful. As it was nearing its conclusion, 180 police marched towards the speakers stand. Then a bomb exploded, "wounding sixty-six policemen, of whom seven later died" (Zinn, 271). One died instantly (see summary at "The Dramas of Haymarket").

Police reacted quickly to the blast, firing into the crowd, killing at least four demonstrators. There are accounts that suggest many of the wounds suffered by the police were due to friendly fire.

The Chicago History Museum's website offers a good synopsis of the effects of the melee:

Acting with overwhelming public support, the police arrested dozens of political radicals. In the trial that followed, eight anarchists were found guilty of murder. After appeals to the Illinois and United States Supreme Courts failed, four of the defendants were executed on November 11, 1887.Howard Zinn list those executed: "Albert Parsons, a printer, August Spies, an upholsterer, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel" (271). Schweikart and Allen mention the conviction for murder and the governor's pardon of three. A Patriot's History does acknowledge, "trials produced evidence that anarchists only loosely associated with the Knights had been involved" (439). Zinn is more specific:

"The Dramas of Haymarket," http://www.chicagohistory.org/dramas/overview/over.htm

Some evidence came out that a man named Rudolph Schnaubelt, supposedly an anarchist, was actually an agent of the police, an agent provocateur, hired to throw the bomb and thus enable the arrest of hundreds, the destruction of the revolutionary leadership in Chicago.

Zinn, 271-272.

Patriot's and People's Contrasts

Howard Zinn does not list specific sources for quotations, but has an extensive bibliography for each chapter. Larry Schweikart and Paul Allen source every quotation. Absent from their citations are the standard left-wing labor histories found in Zinn's list, such as Philip Foner, A History of the Labor Movement in the United States, 4 vols. (1947-1964). Neither text cites The Haymarket Tragedy (1986) by Paul Avrich, which was published several years after Zinn's text. Avrich credits the compositor, Hermann Pudewah, for the word "revenge" at the beginning of Spies' circular.

More telling differences emerge in the spin of these two texts. A Patriot's History offers minimal information concerning the labor movement, and credits the well-known Knights of Labor for the protest activities. A People's History crafts a more detailed account of a multitude of organizations, naming Spies' International Working People's Union, one of several engaged in organizing the strike at McCormick Harvester Works. It highlights the struggle for the eight-hour work day, while A Patriot's History manages to discuss union organizing and strikes without naming a single issue. A Patriot's History does manage, however, "High wages also diminished the appeal of organized labor" (438). In contrast, A People's History emphasizes immigrant labor, noting, "There were 5 1/2 million immigrants in the 1880s, 4 million in the 1890s, creating a labor surplus that kept wages down" (266).

No comments:

Post a Comment